The Dutch central government has announced its intention to conclude a framework agreement for penetration testing around mid‑2026. The tender and the resulting framework agreement will be based on the MIAUW methodology. According to ICT Magazine, the MIAUW methodology is intended to put an end to the “magic and vagueness” that characterise the pentesting market. Transparency, reproducibility and verifiability are presented as the solution to unclear reports and incomparable assessments.

That ambition is understandable. But anyone who looks closely at MIAUW will recognise a familiar pattern: at its core, this is essentially the CCV Pentesting Quality Mark, only more tightly prescribed, with less freedom and a much heavier emphasis on evidential proof.

We are pleased that our earlier blog prompted a critical discussion of the CCV Pentesting Quality Mark. Nevertheless, we do not see the MIAUW methodology as the right way forward, and we question whether it actually addresses the right problem when used as the basis for a framework agreement.

More evidence, but at what cost?

MIAUW builds on the existing CCV quality mark by adding further obligations and documentation requirements. The aim is auditability and legal substantiation. However, gathering that evidence takes time. Time that is no longer spent on the substance of the assessment itself.

This creates a new tension. Clients are led to believe that a MIAUW‑based pentest is automatically of high quality. In reality, it primarily demonstrates that a prescribed process has been followed; it offers no guarantees about the actual depth or creativity of the test. The risk is that the methodology implies a stamp of quality, while substantive differences between providers remain.

Moreover, evidence only has value if someone is able to read and assess it properly. Unless clients employ qualified pentesters themselves, or engage external specialists to review all steps and artefacts, much of that evidential burden remains largely theoretical. Those who genuinely want oversight therefore end up paying twice.

A double burden for suppliers

As penetration testing providers, we already comply with the CCV quality mark. MIAUW adds its own requirements and evidential obligations on top of that. This results in a double administrative burden. Inevitably, the question arises: where does this end?

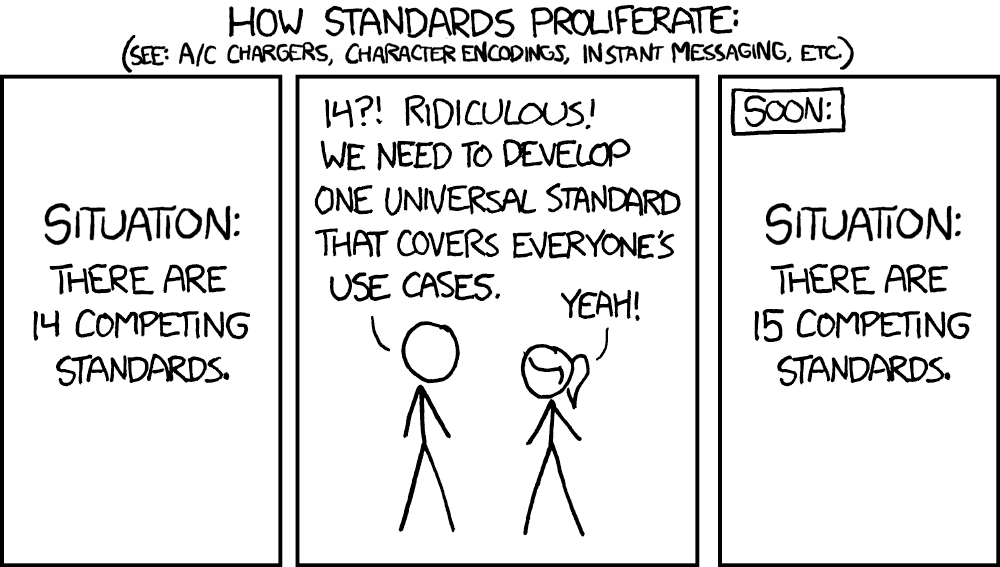

For suppliers, it becomes unclear which framework will ultimately take precedence. Is it the CCV Pentesting Quality Mark, which already serves as a form of quality assurance? Or will the MIAUW methodology become the new standard? What is authoritative, and why was there no discussion about merging the two frameworks to avoid duplication of effort?

We understand that clients want greater control over quality. But every new quality mark or methodology increases administrative overhead, while the core activity - conducting a high‑quality pentest and identifying vulnerabilities - requires time, focus and creativity.

We believe there is a better way. That is why we will publish a new blog tomorrow: “What should a good pentesting tender look like?” In it, we explain how to select providers based on substance and craftsmanship, rather than process alone.

Open source as a strong foundation — provided governance is sound

The open source nature of MIAUW is a positive step: no paywall and full access to its content and templates. However, open source does not automatically mean open governance.

To fully realise the benefits of this openness, there must be clear, independent structures for change management and interpretation. Without such safeguards, the methodology is vulnerable to one‑sided direction and influence.

Tick‑box exercises and the loss of creativity

A familiar criticism of the CCV quality mark returns in an amplified form with MIAUW: the restriction of creativity. A checklist or minimum baseline is useful to ensure that essential elements are not overlooked. However, penetration testing is not a tick‑box exercise; it is a discipline in which unexpected attack paths, intuition and experience are crucial.

The real challenge is whether MIAUW can continue to allow room for these creative, risk‑driven attacks within a rigid process. If the checklist becomes the goal rather than a means, professional expertise is sidelined.

Process is not craftsmanship

A uniform methodology can create a set of conditions, but it cannot replace experience, pattern recognition and contextual understanding. Two testers can follow the same process and still produce vastly different outcomes.

The danger is that clients confuse uniformity of process with uniformity of quality - a dangerous overestimation.

A brake on innovation

We also see market demand shifting towards a continuous pentesting approach, particularly for our clients’ most critical systems. This involves an ongoing model in which findings are reported directly through the client’s ticketing system, allowing issues to be resolved more quickly. The MIAUW methodology does not support this approach, as it does not fit within its reporting format. As a result, we remain tied to outdated PDF reports, despite clear evidence that such reports cause findings to remain unresolved for longer.

In conclusion

We acknowledge the value of transparency and standards. But more evidence and more quality marks do not automatically lead to better pentests. The risk is that MIAUW results in higher costs, increased administrative effort, reduced innovation and a focus on compliance rather than craftsmanship.

That does not make organisations safer, but merely more demonstrably compliant. For that reason, we question the use of the MIAUW methodology as the basis for a framework agreement for penetration testing. How can government bodies genuinely steer on quality instead? We explain this in our next blog: “What does a good pentesting tender look like?”